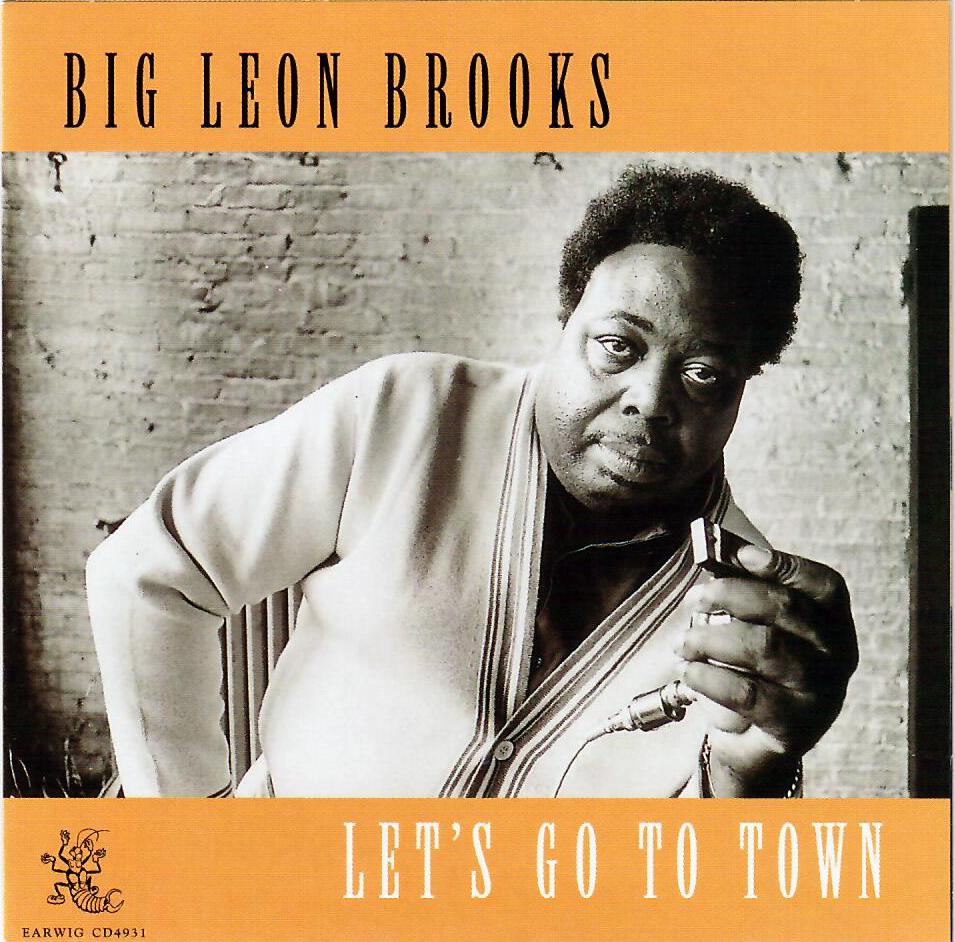

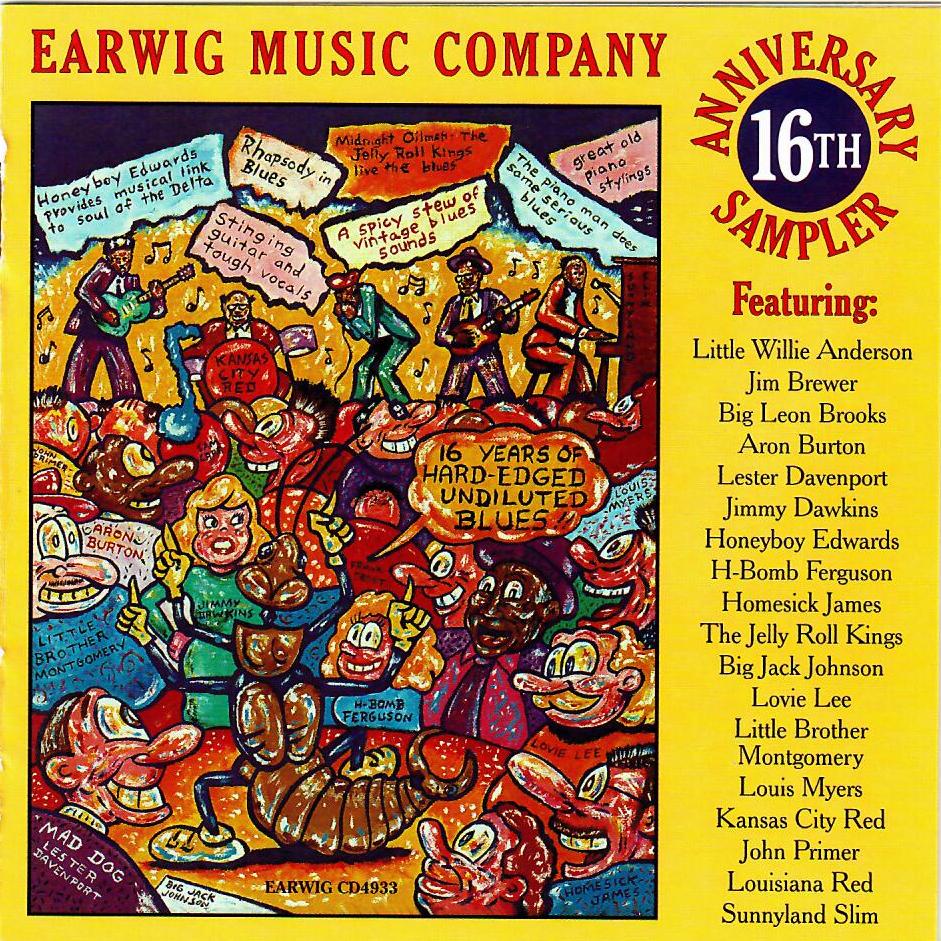

Big Leon Brooks

November 19, 1933 – January 22, 1982

When Big Leon Brooks reappeared on the Chicago blues scene in 1976, it marked the return to action of one of the finest harmonica players from the 1950s blues era. Leon had given up on music for almost 20 years, but he had not been forgotten by the musicians who used to work with him in the South and West Side taverns. And his harmonica playing, still lively and strong, didn’t go unappreciated by the local cult of younger fans and musicians. Leon worked steadily for a couple of years, with a West Side band led by vocalist Tail Dragger and with his own group, recorded a few songs for Alligator’s Living Chicago Blues series, and cut this album for B.O.B. Records. But recurring heart problems sidelined him time and time again, and in an all too typical and tragic blues scenario, Big Leon died in Chicago on January 22, 1982, before he ever saw his album released. Just the day before his death, unanswered questions were still on his mind: “I want to know, could I have made it – if I hadn’t run into bad luck or if I had continued when I was young – would I have been able to make it? I’m 48 years old now and if I didn’t make it when I was young, I don’t think I’m gonna make no money now out of it. It’s just the idea that I want to know is the quality there, is the music good enough? Do the peoples like it? Do they understand what I’m doin’? If I know this, then I’ll be satisfied.”

Leon died with the satisfaction of at least knowing that his album would soon give the world a chance to hear and understand what he’s worked for over so many years. Whether he would have made it in music if he hadn’t got disgusted back in 1957 or if his health hadn’t been so damaged – by drugs in those early years and by later heart and lung ailments – we’ll never know, because talent and success unfortunately do go hand in hand in the blues business. But the quality of his musicianship was never really in question. As Jimmy Rogers says, “He was heavy. When he was with me he was goin’ real hot. If he hadn’t been tied up in that stuff, we probably coulda made it way on up the road.”

Jimmy Rogers’ band was only one of the several noted Chicago blues combos that featured that heavy Big Leon harmonica sound during the mid-1950s. Leon also worked with Freddie King, Robert Nighthawk and Otis Rush, filled in as a harp player in Muddy Waters’ group for a while, and gained valuable experience by playing with Little Walter’s band on occasion. “Little Walter was the hottest thing on the scene, and so everybody was sounding like Little Walter,” Leon recalled. “I idolized the man, I loved the man, you know, because he was a genius.”

Before he’d ever heard of Little Walter, Leon was inspired by the King Biscuit Time radio broadcasts of Sonny Boy Williamson that he heard while growing up in Sunflower, Mississippi. Leon was born on the Rabbit Foot farm near Sunflower on November 19, 1933, and started playing harmonica with some stern encouragement from his grandmother: “She gave me some money to buy some clothes and I spent it all on harmonicas. At the time harmonicas cost like 25 cents, and I spent the whole five dollars, so she gave me a lickin’. She told me that I had to learn how to play, and every time I hit a bad note she’d bop me! I never really had nobody to teach me a lesson. I learnt this all by listenin’ at the radio.”

Leon’s family moved to Chicago when he was only six, but on summer vacations Leon returned to visit relatives in Mississippi and Arkansas, where he saw Sonny Boy, Elmore James, Junior Parker, Boyd Gilmore and others, including Leon’s distant cousin, Charlie Booker. In Chicago, Leon began playing harp with some young South Side schoolmates and soon started blowing on the streets of the Maxwell Street Market and slipping into the blues taverns when he could. “I was playing mostly on Sonny Boy Williams’ style,” Leon said. “But I got the technique from listenin’ at Walter play. ‘Cause they was always my idols. After I became a teenager, I met Walter and he really inspired me.” Although his playing was often compared to Little Walter’s, Leon asserted, “Sure, I’ll hit some licks like he did, but it wasn’t completely the same thing. I always created my own music. I got my own style of playing. I got a more gross tone than Walter. His thinking ability is more faster but my town is more grosser.”

Like Little Walter, Leon picked up a lot of ideas from listening to saxophone players: “Lester Young, Prez, Gene Ammons, Sonny Stitt, Eddie ‘Lockjaw’ Davis, all those guys, I loved ‘em. I loved saxophone music. I’d try to use some of the ideas from saxophone for the harmonica. In the early ‘50s, mostly it was all jazz then, and if a musician was playin’ harmonica, he had to swing his harmonica. Harmonica players really had to go into something’ like a sax based sound then, because they was getting’ away from the old original cotton pickin’ blues. So every harmonica player that had an idea in his head or could think or could blow was trying’ to do somethin’ like a saxophone was. And quite a few of ‘em wasn’t doin’ it. But thank God for the ones that could do it. And I think Walter, he was the tops on doing that. I think I did pretty good.”

In between stints at the 703 Club, the Zanzibar, Mr. Ricky’s, Theresa’s and many other local clubs as sideman, Leon fronted his own band. But things started to fall apart – Leon complained that his band members were unreliable, club gigs were harder to come by, and recording opportunities were even scarcer since Little Walter and Sonny Boy had the market cornered on the blues harmonica at Chess Records. The fast life was taking its toll on Leon, too, according to Jimmy Rogers, who saw his promising young harp player enter the hospital for treatment and didn’t see him again for several years. Leon eventually found a job and raised a family but put his harmonica aside except for practicing at home or playing with friends.

“I never really got a chance to do what I wanted to,” Leon explained, “because I got all disgusted with music. I couldn’t keep a band together. So I just quit. I didn’t go to no clubs. I just stayed at home and listened at the radio or played the hi-fi. I was workin’ on a job as a truck driver. I just practiced at home for myself and I kept myself together with the music.”

Leon’s harmonica playing was still intact in 1976, when he was living in a West Side apartment above Crawford’s Lounge. Venturing downstairs one night, he found his old friend Lester Davenport playing in the tavern with Tail Dragger. With some prompting from Lester, Leon went back upstairs for his harmonica, returned to blow a few numbers with the band, and soon his retirement was over. His first gig with Tail Dragger at David & Thelma’s Lounge was followed by jobs at the Golden Slipped, Kingston Mines and several other clubs, plus a trip to Mississippi for a few club dates back in his old Delta stomping grounds. As a bandleader or as a featured guest, Leon found a new crew of young musicians to support him, such as Paul Cooper, Dimestore Fred, Freddie Dixon and Pocketwatch Paul. This time around, Leon was pleased with his band and with the recognition that was coming his way at last. But his second career turned out to be even shorter than his first. His health permitted him only a few chances to perform during the last year or two. Yet sheer determination gave him the strength to come up with a fitting album to leave as his final contribution to the blues.

It’s an album of Leon’s own originals, recorded with all-star Chicago blues veterans. Leon gave his all to this project, and it’s a record he would have been proud to see. “Only thing I’m hopin’,” he reflected, realizing the end was near, “is that my music will enlighten some young person to play music, to be conscientious to the blues like I was when I was a kid. And I hope that my music leave a mark on the world. So they could say, ‘Well, old Leon was a good harmonica player. He was a good musician.’ I want to leave it with y’all, man”

-Written by Jim O’Neal