On Memorial Day 2013 it is fitting that I commemorate the legacy of three Earwig recording artists who served in the U.S. Military. There may be others on Earwig who did serve, though I am not aware of them.

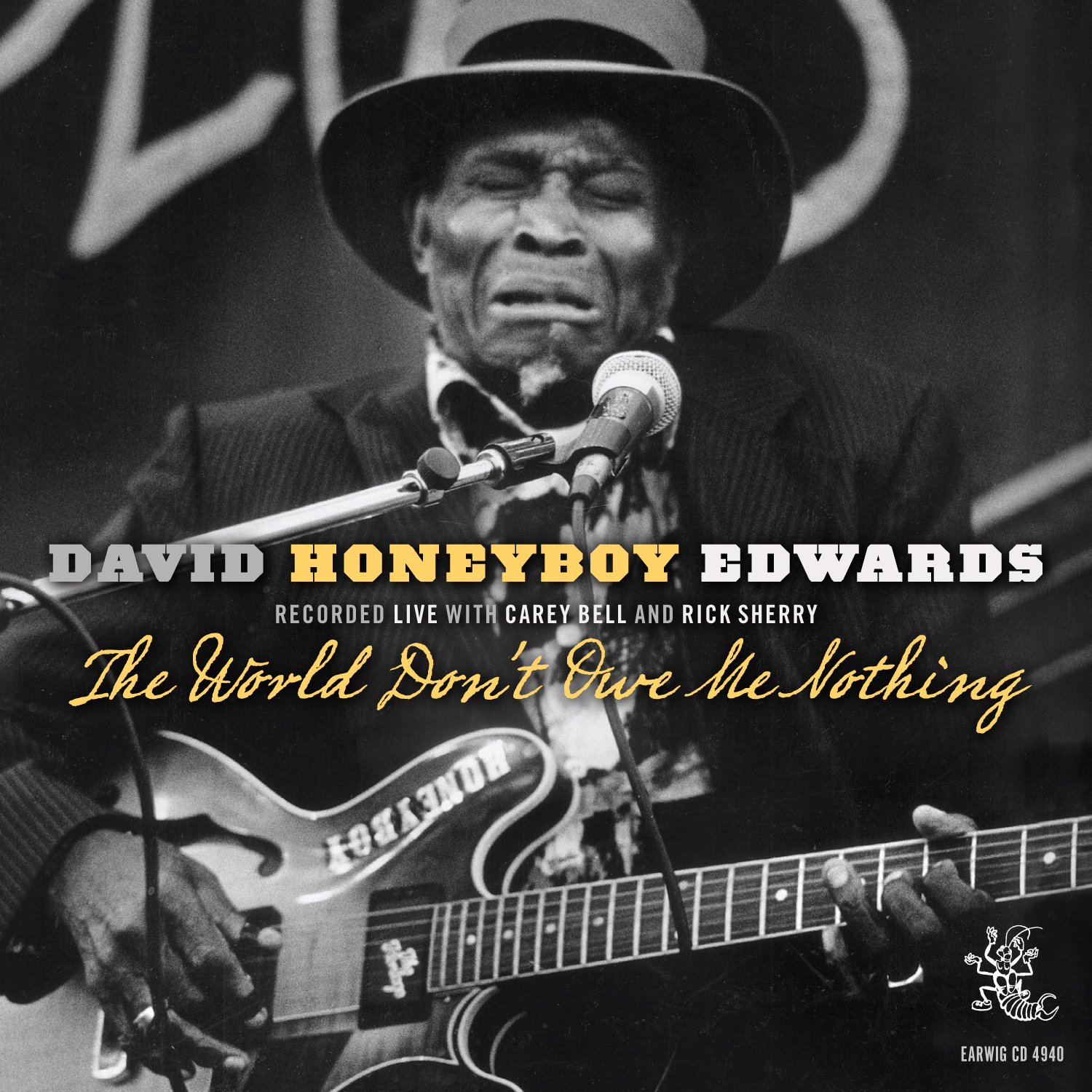

Homesick James Williamson, whose real name was William Henderson, was born in April 1910. He served in World War II in the Army and sustained a leg injury, which caused him to limp slightly, as one leg ended up shorter than the other. Homesick, as he came to be called by musicians and friends, perpetuated a mysterious image, rarely discussing details of his early life. He had a slightly Caribbean lilt to his accent, and often spoke in an almost mumbling manner which made it hard to understand him. He sometimes broke into fractured Spanish. He periodically moved, without much prior notice to anyone. During the 23 odd years that I knew him, he moved numerous times around Chicago, then to Nashville, Atlanta, Georgia, on to northern California, then to Covington, Tennessee and finally to Springfield, Missouri. Consequently another of his nicknames was Lookquick. Just as Honeyboy Edwards used to say “The world don’t owe me nothing,” Homesick used to tell folks “Look quick, ‘cause tomorrow I may be gone.”

In fact, I took him to renew his passport in Chicago around the time of his Earwig recording session, and while I was waiting in my car several hours for him to come back from the passport office, he decided without telling me, to take off and take a cab back to his apartment over Rosa’s Lounge. He later told me that he was aggravated with Mama Rosa, his wife, who had decided to ride in the car with us because she wanted to spend some time with him. They had separated several years before and Homesick had moved out of town. During the time he was in Chicago for the recording session, he was staying with her. That was typical of Homesick, to make a seemingly spontaneous decision based on his feelings at the moment, without regard to the decision’s impact on those around him.

Homesick was a proud man, who in most instances stood by his word. He also took pride in his ability to build as well as repair guitars, and in his musical knowledge. He was an outstanding guitarist, whose style was an amalgam of Tennessee and Mississippi Delta blues and Chicago 50’s electric blues. He was a contemporary of Memphis Minnie, John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson, Henry Townsend, Yank Rachel, Sleepy John Estes, Lonnie Johnson, Big Bill Broonzy, Sunnyland Slim, Elmore James and others. Homesick never quite got as much recognition as those great musicians. He is best known for playing with Elmore James, his cousin and his best known recordings are similar in style to Elmore’s. On his best days, he certainly could play as well as any of them.

Playing with Homesick James was a challenge, because he tended to jump time, meaning that he made turnarounds somewhat unpredictably, so band members had to be able to anticipate what he might do. In that respect his playing was like Honeyboy Edwards’ style, though the two of them were unpredictable in different ways. I had the opportunity to produce one album of Homesick’s music, which I titled Goin’ Back In the Times, a phrase he used to introduce one of the songs on the recording. That album was supposed to be half a band album and half a solo album. He and I had agreed to hire some of the best Chicago musicians, who knew him and his style, to play on the session. So Homesick and I agreed on Sunnyland Slim – Albert Luandrew – on piano, Bob Stroger on bass, Robert Covington on drums, Lester Davenport on harmonica. Both Stroger and Covington were in Sunnyland’s band at that time. Lester had played with lots of folks, and had gotten his early tutelage from Homesick in the 1950s.

The day before the session, we had a rehearsal scheduled at my house, and Homesick refused to come to it, though I had put him up at a motel close to my house. When I went to pick him up, the musicians were already at my house. He gave me no explanation, he just would not rehearse. The next day, August 27th 1992, in the studio at Delmark, Homesick early in the session, got into an argument with Bob, Robert, and Lester, claiming that they had been playing his music wrong. Homesick started cursing at these guys, and Stroger and Covington, though they knew Homesick was mercurial, verbally pushed back, saying that he was the one messing up, and that they were not going to take his verbal abuse. Lester, on the other hand, was more pragmatic, so he tried to cool things down so that we could finish the session. I expect that Sunnyland did the same as Lester, though I have no recollection of his reaction to Homesick’s obnoxiousness that day. I was freaking out, because I was spending a lot of money for the session and I was afraid of getting a bad session. In fact I did not use any of that session on the album and have not listened to it since.

Back at the motel, Homesick acted as if nothing was wrong, though I was both very angry and hurt. Homesick just sat on his bed, playing Lonnie Johnson licks on his guitar as I vented. At that moment, when he was playing so beautifully, I felt as if he was intentionally messing with my mind, since in the studio he had not played like that. I extracted a commitment to him to play that type of material the next day, when we were scheduled to record solo and duo tracks, with Honeyboy Edwards as a guest on a few tracks. Fortunately for me and for my label’s body of work, on the second session, Homesick did what he said he would. He played some tunes he had not recorded before or since, with some beautiful licks covering his wide range of styles. He also waxed nostalgically on tape about his old friends Sunnyland Slim, Yank Rachel and Honeyboy Edwards, who played with him on a few tracks. Honeyboy had met Homesick in 1937 at the Tunica, Mississippi train station.

What I ended up with was a beautiful traditional blues record, unlike most of the other recordings Homesick did in his lifetime. I love the record. One of these days, now that Protools software makes it so easy to edit and improve recordings, I will revisit the multitrack band recordings. Maybe I will discover something better than I remember from that very upsetting session with those blues masters when Homesick went off on them.

My last memory of Homesick James is booking and watching Homesick on his last gig, the Maryport, England Blues Festival, the last weekend in July 2006. Homesick, Honeyboy Edwards with me on harmonica, and Robert Lockwood with his bassist Gene Schwartz, played that gig. Homesick was not feeling well, but like the trooper he was, played a 30 minute solo set, looking his usual dapper self in his suit, shined leather boots, and hat to match. He had stayed in bed most of the time over there, except to play his set and do a video interview with a documentary filmmaker. By the time we were ready to come back home, his feet had swollen such that he could not wear his boots. I offered him my purple Crocs so he would be more comfortable traveling. He wore those Crocs home, and got progressively sick that fall. He died at the age of 96 in a hospital in Springfield, Missouri December 13, 2006. His funeral was held in Covington, Tennessee, where his sister lived. He was preceded in death earlier that year, by his friends Henry Townsend on October 2, 2006 , Snooky Pryor on November 10, 2006, and Robert Lockwood on November 30, 2006.